|

| There comes a journey . . . |

For me the best part of the conference was the wonderful atmosphere we created about community and sharing and being open with each other. By attending, by coming, by overcoming obstacles of many kinds, we created something truly special together. We overcame travel and distance issues. Sometimes we overcame political or professional hurdles. We overcame philosophical or pedagogical differences. We overcame language barriers. Together we shared moments of connection. We shared photos and videos and stories of our students and our teaching lives. We asked questions and sought answers for our teaching puzzles. We embraced new ideas and connections, made new friends from places far away, and shared our joy of belonging to a vital and uplifting profession. Most of all, we reaffirmed our commitment to a philosophy of education and a community of personalities who share a deep love of children, a desire to contribute our time and knowledge to the world, and a shared vision of a better world through our work as teachers.

There were 3-4 days of many topics and presentations. Mimi Zweig (www.stringpedagogy.com) presented an intensive course about establishing a healthy foundation of violin playing with scales, etudes, and repertoire. We examined closely how basic posture setup could be reinforced with the addition of supplementary repertoire and technical materials. We discussed shifting ideas and techniques for eliciting a beautiful tone and working with students in an ensemble setting. We observed individual student lessons and how these ideas would be drawn into a teaching situation.

The evening presentations were designed to promote discussion and thought. One evening we watched a film about students in Mimi Zweig’s youth music program at the University of Indiana in Bloomington, Indiana. The video documented the growth and aspirations of several of Mimi Zweig’s most advanced high school students and inspired many of us teachers to return to our rooms to practice ourselves or to retire to the local pub together as a group to share our questions and discussions further.

|

| David Andruss |

Other presentations included such diverse topics as how a music teacher might effectively use the Internet at a low cost (Wolfgang Fischer and Dr. Ingrid Schlenk), how to prevent shoulder and neck pain while playing the violin (Ursula Benz), Autism Spectrum Disorder (Dr. Ingrid Schlenk), teaching points for early Suzuki violin book 1, Suzuki building blocks, sound production and intonation as they relate to the Paul Rolland and Suzuki pedagogies (Dr. Claudio Forcada), nurturing parents into partnership with Suzuki teachers (Paula Bird and Sue Hunt), group class creativity and music pieces to foster technique in a group setting (Isabel Morey Suau), movement and rhythm (Gino Romero Ramirez), violin literature from Poland (Elżbieta Wegrzyn), and games to spark interest in review (Agathe Jerie). And all of these wonderful presentations were translated by the capable Verena Sophie Lauer.

|

| Charles Krigbaum |

|

| Heidi Curatolo & Kerstin Wartburg |

|

| Veronika Kimiti, Kerstin Wartberg |

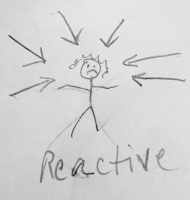

My favorite conference takeaway was that we are not alone as teachers, nor are we to be isolated and separated from each other by artificial and nonproductive constraints. We all love music and teaching and wish to share our joy of music with the students who have come to us and asked to share our teaching joy and experience with them. The teachers who attended and presented at this conference frequently expressed their interest in connecting with each other as nurturers of young students. We shared the same philosophy that what we teachers do in our profession is too important to try and limit it in a box. Rather than look for ways to exclude people (teachers and students, organizational members or nonmembers, Suzuki or nonSuzuki), we wanted to look for ways to connect with each other. We wanted to focus our efforts on inclusion to the community rather than exclusion.

I believe that this is what Dr. Suzuki wanted. I believe that he expected us to absorb his ideas about philosophy, teaching, learning, and character development and then run away with them down the road until we reached everyone with these ideas. I believe that he encouraged the teachers who attended his presentations, workshops, and trainings to keep growing and to keep looking for answers to solve teaching problems.

"Man is the son of his environment," Dr. Suzuki said. I believe Dr. Suzuki served as the perfect role model for how to develop philosophy and search for new ideas. Dr. Suzuki himself experimented as a matter of course, and he showed us the way and provided us with the model example of how we could continue to develop. He did not close doors to experimentation or membership or training. He opened his arms wide and talked about nurturing, love, growth, and development through the vehicle of music and teaching, and he included everyone. His mission for the world was too great to be limiting.

I was not blessed to have met or study personally with Dr. Suzuki, but I have read his materials, books, and articles. I am an avid reader of all things Suzuki-related, and I appreciate the time and effort taken by those early teaching pioneers in the Suzuki community who wrote books and articles about their experiences with Dr. Suzuki and his workshops and trainings. It is my fervent hope and mission that we will all share our belief in the universal message that all "children have talent" and "character first, ability second."

I returned home from the conference with a joyful heart and a soul at peace that I am where I need to be as a teacher in a global community. The conference once again renewed my sense of belonging to a mission and a teaching philosophy that is larger than I am, that what we do as teachers is so much more important because of the global impact of our influence on students and parents and family and community. We shared our love of teaching with each other, and we welcomed everyone's ideas and experiences.

I look forward to next year's conference November 2-5, 2018. Please consider joining me.

Until next time,

Until next time,

Happy Practicing!

----- Paula -----

© 2017 by Paula E. Bird