"I can't do it!"

"I'm so stupid!"

"I'll never be able to get this!"

"I'm just not very good at this."

When I trained for the marathon in 2005-6, I learned that it was imperative that I keep my mind in a positive mode. I found it easier to stay the course in my training and discipline if I kept my mind in a healthier, more upbeat place, because whenever any negativity entered into my sphere, I noticed that it had a detrimental effect on my psychological ability to push through and keep going.

During my training, I picked up many helpful tricks to stay in this happier mental state, and I found these tricks quite useful in the musical arena as well. Most of these simple tricks related to a simple tweak in my focus and awareness of the language I chose to use aloud and to myself.

"You can do this, you know you can."

|

| Yes! |

"You're a person who perseveres when things get tough."

"You have the discipline and strength to finish this."

"You are prepared for this, so relax and let the training take over."

I said these affirmations, especially the first one, frequently every day. What I discovered is that the affirmation would pop into my head several times all on its own. It became a part of my self-talk on a regular basis, and I noticed that my attitude stayed positive and strong as a result.

But how do we get to this stage? For some of us, our self-talk has dipped so low, that we are unaware of how weighty it has become. It pulls on us, gnaws on us, and ultimately drags us down to an unpleasant place where things seem so hard and impossible to accomplish. How do we fix this negative self-talk habit? I have a few suggestions.

Here are three easy steps that you can take to help you notice and change your language choices.

Change your Physical State

Changing our physical state will often change our mental state. For example, when I am angry or frustrated, I notice that my shoulders, upper back, and back of the neck are tense. I hold my breath. When I adjust these tension points and take a slow breath out and then in, my mental attitude responds as it relaxes and drifts toward a more positive state.

Notice what your physical state is the next time you catch yourself saying something negative. Are you holding your breath? Are you squeezing a muscle somewhere in your body? Are you clenching anything? Are you smiling? Whatever you are doing, change it to something else. I find that smiling is the fastest way to change a negative physical condition. I make it a practice to smile at the top or bottom of every flight of stairs at work, from the initial stairway that leads down to the front door of my workplace to the inner staircase that connects both floors of the building. Every time I reach the bottom or top of the staircases, I remind myself to smile. This is a habit that I have built over time, and I think that it has helped immensely to alter my face into a happier one when I greet my colleagues and students within my workplace.

But it Doesn't Matter

This suggestion comes from one of my favorite books. Although this book is devoted to marathon training for non-marathon runners, I find that much of the book has some very useful tips for musicians. The book, Non-Runner's Marathon Trainer by David Whitsett, Forrest Dolgener, and Tanjala Kole, has three parts to each chapter:

- The first part is devoted to the psychological or mental aspect of training and preparing for a marathon.

- The second part advises things related to the physical aspects of training.

- The third part recounts personal stories and advice from runners involved in the training program.

What I found most helpful in this book from a musician's standpoint was the psychological discussion at the beginning of each chapter. When it comes to altering your language choices or focus, I highly recommend this book as one of the tools you might use because of its wealth of information contained at the beginning of each chapter. And the training program (4 runs per week) is pretty darn good too.

One very useful suggestion from the marathon training book was the phrase, "but it doesn't matter" placed at the end of every complaint or negative thought. For example, I might start whining because I am having trouble with my coffee pot. "But it doesn't matter!" I will exclaim. Then I will argue with myself for a few more sentences: "yes it matters! I need to have my coffee in the morning without fussing with the coffee pot!" I pause and remember what I am supposed to do. "But it doesn't matter," I will remind myself to say aloud.

It really does not matter unless you believe it does, and by reminding yourself that it does not matter, you will remind yourself to overcome whatever frustration is in this moment. Since we routinely overcome many such problems in our lives, this teensy reminder goes a long way to refocus our attitude, belief, and view of ourselves -- that we can do this. After reminding myself a few times that my complaints really do not matter, I will notice that my body completely relaxes with the change in thought and attitude.

Modify Your Behavior (the Positive-Negative Marble Jars)

One studio family came up with a clever idea to help modify their child's language behavior. The daughter was in the habit of arguing a lot without really meaning to argue. She would enter into conversations with a conflicting viewpoint, or she would answer "yes" and then follow it up with "but" or "no." Her parents came up with a behavior modification scheme to help the daughter to recognize when she was doing these types of behaviors, and the parents helped her to find a concrete way to record these negative or positive behaviors. The parents hoped that by recording the language choices the daughter made, that the daughter would then refrain from the unwanted negative language in favor of positive responses. Instead of saying, "no," "but," an excuse of any kind, or any other negative words, the parents encouraged her to say, "yes, and," "okay," and "may I" instead. For example, here is a possible conversation before the behavior modification scheme:

Parent: "I think it's going to be a nice day."

Child: "Yes, but it's going to rain later."

Teacher: "I think your left hand could be more relaxed so that your wrist is flatter rather than bent."

Student: "But I'm holding it relaxed!"

Parent: "Can you take out the garbage later?"

Child: "No."

If you notice, there would not be much to say after those brief exchanges. After the behavior modification, the above conversations might go like this:

Parent: "I think it's going to be a nice day."

Child: "Yes, and it might rain later too."

Parent: "Oh that might complicate things! We do need the rain for the garden though."

Teacher: "I think your left hand could be more relaxed so that your wrist is flatter rather than bent."

Student: "Okay, let me try that. Does this work better?"

Teacher: "Yes, that's better. Can we work together to see if your wrist can relax even more?"

Parent: "Can you take out the garbage later?"

Child: "May I do it after dinner rather than right now?"

Parent: "Of course, that would be a terrific help!"

Notice that it feels more comfortable to continue with the conversation when there are positive responses.

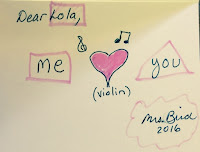

Here is a picture of the positive-negative jars that the parents used to help their daughter become more aware of the language choices she made. If the daughter said something negative or positive, then she would put a marble in the appropriate jar. Notice how many positive marbles there are after only a few days of this exercise! At the next lesson, the daughter was very eager to tell me the exact number of positive versus negative marbles that she had in her jars.

|

| Positive and Negative Marble Jars |

One of my other posts discussed what a performer might say after a recital or other performance. If you would like to read that post, click here.

If you are interested in the marathon book, click here. Please note that this is an affiliate link, meaning that it will be no additional cost to you and you are under no obligation to purchase this item, but if you are already in the market to buy this book, I will get a financial benefit that will go to support the blog and the production of the podcast. I appreciate your help so that I can avoid putting advertisements on the blog.

As a reminder too, if you have not yet subscribed to my newsletter, please do so or send me an email and I will add you to the mailing list. At the moment I send the newsletter out twice a month and include links to articles and podcast episodes that you may have missed. As always, I greatly appreciate my readers and all of their helpful suggestions and comments!

Happy Practicing!

----- Paula -----

© 2016 by Paula E. Bird